We talk and talk (and talk) about how to behave — and even how to survive — in the digital world. And we hope it’s not in vain, that our readers learn from us and then teach their friends and relatives. It’s really important.

But we sometimes take for granted a common knowledge of some specific terms and expressions. So today we’re going back to basics to tackle three fundamentals of antivirus.

1. Signatures

Antivirus databases contain what are called signatures, both in common usage and in writing. In reality, classic signatures have not been in use for about 20 years.

From the very beginning, in the 1980s, signatures as a concept were not clearly defined. Even now, they don’t have a devoted Wikipedia page, and the entry on malware uses the term without defining signatures, as if were such common knowledge as to go without explanation.

So: Let’s define signatures at last! A virus signature is a continuous sequence of bytes that is common for a certain malware sample. That means it’s contained within the malware or the infected file and not in unaffected files.

Nowadays, signatures are far from sufficient to detect malicious files. Malware creators obfuscate, using a variety of techniques to cover their tracks. That’s why modern antivirus products must use more advanced detection methods. Antivirus databases still contain signatures (they account for more than half of all database entries), but they include more sophisticated entries as well.

As a matter of habit, everyone still calls such entries “signatures.” There’s no harm in that, as long as we remember that the term is shorthand for a gamut of techniques that make up a much more robust arsenal.

Ideally, we’d stop using the word signature to refer to any entry in the antivirus database, but it’s so commonly used — and a more accurate term doesn’t yet exist — so the practice persists.

#MachineLearning is fundamental to #cybersecurity. Here are some interesting facts about them: https://t.co/5BV78lc737 #ai_oil pic.twitter.com/6frMGOzUgL

— Eugene Kaspersky (@e_kaspersky) September 26, 2016

An antivirus database entry is just that: one entry. The technology behind it could be either a classic signature or something super-sophisticated, innovative, and targeting the most advanced malware.

2. Viruses

As you might have noticed, our analysts avoid using the term virus and prefer malware, threat, and so on. The reason is that a virus is a specific type of malware that exhibits a specific behavior: It infects clean files. Between themselves, analysts refer to a virus as an infector.

Infectors enjoy a unique status in the lab. First, they are difficult to detect — at a glance, an infected file seems clean. Second, infectors require special treatment: almost all of them need specific detection and disinfection procedures. That is why infectors are handled by experts who specialize in this field.

So, to avoid confusion when talking about threats in general, analysts use umbrella terms such as “malicious program” and “malware.”

Here are a couple of other classifications that may come in handy. A worm is a type of malware that can replicate itself and break out of the device it initially infected to infect others. And malware, technically speaking, does not include adware (intrusive advertising software) or riskware(legitimate software that can inflict harm on a system if installed by malefactors).

3. Disinfection

Lately, I’ve been seeing a lot of what I hope is not a common misperception: that antivirus can only scan and detect malware, but then a user needs to download a special utility to remove the malware. In fact, special utilities do exist for certain types of malware: for example, decryptors for files affected by ransomware. But antivirus can cope on its own — and at times it’s the better option, provided access to system drivers and other technologies that cannot fit into a utility.

So, how does malware removal work? In a tiny percentage of cases, a machine picks up an infector (typically before antivirus is installed; infectors seldom slip through an antivirus’s defenses), the infector acts on some files, and then the antivirus goes through any infected files and removes the malicious code, restoring them to their original state. The same procedure is implemented when you need to decrypt files encrypted by ransomware, commonly detected as Trojan-Ransom.

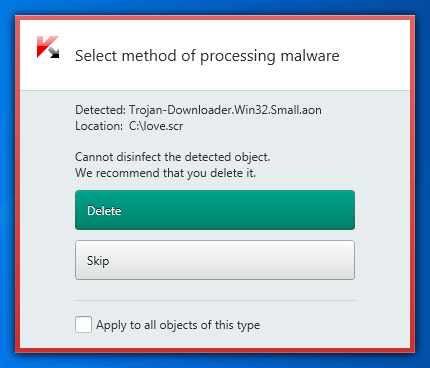

As for the rest — the vast majority, perhaps 99% of cases — the malware is caught before it can infect any files, the process consists of simply deleting the malware. If no files were damaged, there’s no need to restore anything.

There is one exception here, though: If the malware is not an infector – for example, if it is ransomware – and is already active in the system, the antivirus switches to disinfection mode to make sure the threat is gone for good and won’t come back. You can learn more about the process here.

That exception usually happens for one of two reasons:

- The antivirus was installed onto an already infected computer. You know, the usual wrong sequence — first get infected, than decide it’s time to do something about protection.

- The antivirus marked something “suspicious” rather than “malicious” and started to closely monitor its activities. As soon as the malware becomes clearly malicious, the antivirus rolls back all malicious activities (noted during that period of monitoring). For example, the antivirus could restore encrypted files from instant backup copies if the PC was attacked by ransomware or an infector.

Conclusion

That’s it for today. I hope you now:

- Know that “signatures” today are, basically, any antivirus database entries, including the most advanced ones.

- Are more familiar with the different types of malware.

- Understand that the process of disinfecting a computer or device is well within an antivirus program’s competence — and why it’s important to keep the System Watcher component in your antivirus program active to analyze the behavior of suspicious files.

Antivirus

Antivirus

Tips

Tips