It is inevitable that sometime in our lives either illness or injury will send us to the hospital to be cared for by a doctor or team of doctors. While years of schooling and practice have us trusting doctors, we also have to put our trust into the high-tech medical devices that can help identify or treat what ails us. A byproduct of this is that we also have to entrust our safety and well-being to the hardware and software developers, who created the medical equipment used by doctors, as well as the system administrators who adjust it.

As the years progress, medical equipment is becoming more and more complex and interconnected and the hospitals are getting more and more packed with these devices. All these sensors and smart machines require complex software. As cybersecurity is usually not among the top priorities for medical equipment manufacturers, these devices inevitably have security holes. And if there are bugs and vulnerabilities, a breach will come. But is hacking hospital that dangerous?

So, what’s wrong with a hospital hack?

One word answer: everything

First of all, cybercriminals can exploit software vulnerabilities to steal patients’ data or infect the network with malware (not the worst scenario).

"I hate hospitals" @61ack1ynx #TheSAS2016 pic.twitter.com/K7PBQjKfp5

— Andrey Nikishin (@andreynikishin) February 9, 2016

Hackers can also alter the data in the patients’ electronic health records: turn a healthy person into a sick one or vice versa, change some test results or dose strength — and that can seriously damage patients’ health. It’s also possible to adjust medical devices in the wrong way and thereby break expensive equipment or — once again — hurt the patients who undergo treatment with the help of these machines.

From something in mind to something in kind

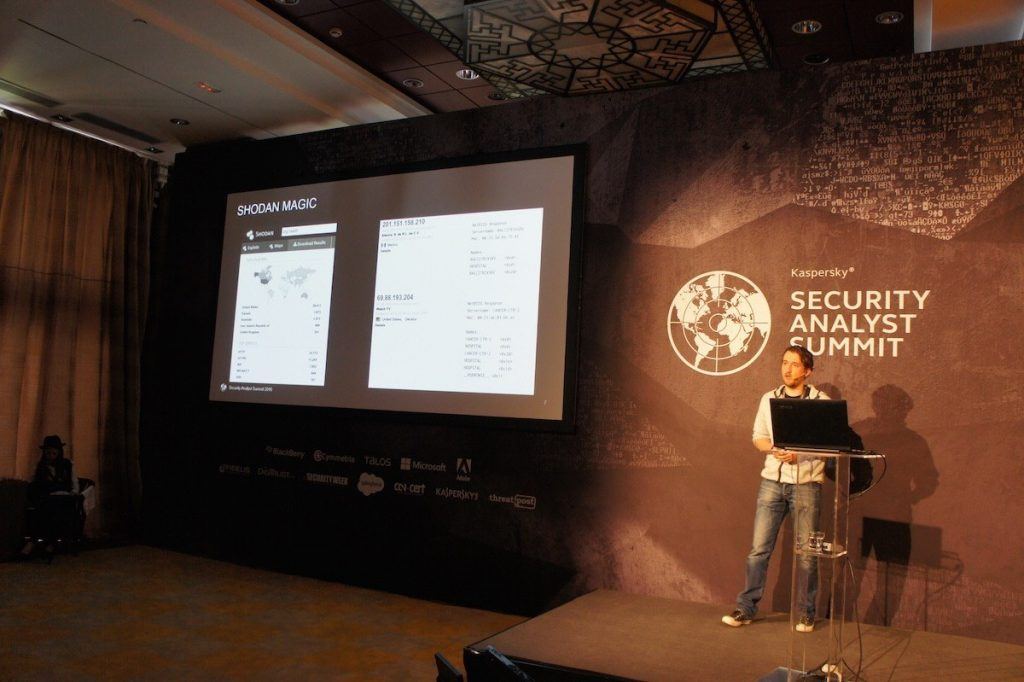

At the Security Analyst Summit 2016 Kaspersky Lab’s expert Sergey Lozhkin revealed how he had actually hacked a hospital.

One day Lozhkin was using Shodan (this is the search engine for the Internet of Things) and eventually came across medical equipment of a hospital, which seemed somehow familiar — it turned out that it belonged to a friend of his. Lozhkin explained the situation to the owner and the duo decided to make a secret penetration test, and find out if it was possible for somebody to hack the hospital.

The two arranged that nobody would know about the test apart from the senior managers. The last ones secured real patients and their data from any potential damage, caused by the “hacker.”

The first attempt failed: Sergey could not hack the hospital remotely, as in this case the system administrators worked just fine.

But then Sergey came to the hospital and found out that he could connect to the local Wi-Fi, which was not properly set up. He managed to hack the network key and that gave him access to pretty much everything inside, including a number of devices for data storage and analysis. The device that caught Sergey’s attention was an expensive tomographic scanner, which also could be accessed form inside the local network. The device stored a great deal of data about different — fictitious — patients (as real data had been previously secured by the management).

Having exploited an application vulnerability, Sergey accessed the file system and correspondingly, all available data in the scanner. If Sergey was a real cybercriminal, at this point he would’ve been able to do almost everything: change, steal or destroy the data and even crack the tomographic scanner out of service.

As a temporary measure Lozhkin recommended the hiring of a competent system administrator, who would’ve never connected a tomographic scanner and other important devices to a public network. But this is not a real solution for the problem as the ones to blame here are first of all the developers of this machine. They had to care more about cybersecurity of their product.

Who is to blame and what we should do?

Lozhkin’s report shows how much needs to be done in terms of medical equipment cybersecurity. There are two groups of people who need to be alarmed by this question, more specifically — the developers of medical equipment and the hospital management boards.

https://twitter.com/samgadjones/status/697024521166004228

The developers should test their devices for security, search for vulnerabilities and ensure they are all patched in a timely fashion. The management groups should care more about their network security and be certain that no critical infrastructure equipment is connected to any public network.And both groups really need cybersecurity audit checks. For hospitals these can be fulfilled as penetration tests, for developers — as all round security tests, which should be performed before the commercial distribution of their products.

breach

breach